“We’re all touching the elephant. …. Immunologists would touch the elephant by doing antibody assays. The bioinformaticists will do a big genetic screen. The epidemiologists look at 800,000 medical records. And so you almost have to do this very orthogonally, you know, to have different approaches. Any serious evaluation of causality needs all those pieces to fit together.”

Bob Morris: How do you explain Ascherio’s results without there being a sort of a causal relationship, that you must have had an EBV infection or else you didn’t get MS?

Steve Jacobson: I agree with you, and I’ve always agreed that there is some association that’s going on. Whether that means it’s the initiator or the ongoing trigger is not clear. But again, I go back to this idea that this involves a genetically susceptible individual, and we don’t know what those genes are yet that get triggered by this or other bugs, that lead to some immune dysregulation. It’s that triple whammy that equals MS. This is how I think about it, actually. And we know that a lot of our immunosuppressive drugs really work in MS, right? So, there’s clearly an immune component to it.

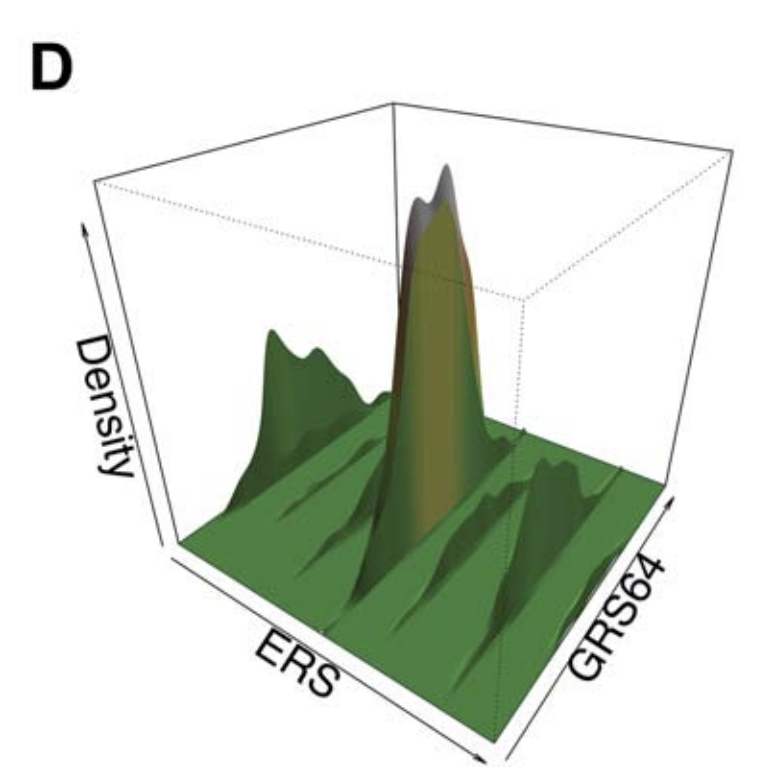

There is a genetic component. We’ve been trying to look for a genetic signature, right? If I take your blood, can I find that you’re at risk for getting it? We haven’t found that yet, and this is another good example. You’re aware of the epidemiological aspects of the GWAS (Genome Wide Association Studies), right?

I’ve been through this in the MS field. When you looked at 100 patients, you got some little hint, but nothing ever worked out. So, then you looked at a few thousand patients and then you found some other genes. But they didn’t hold up very well because they would give you LOD scores of like 1.31, 1.32, 1.33. They didn’t hold up in 1,000, so they looked at 10,000, and now it’s getting a little bit better but still not there. They had to look at hundreds of thousands of cases. That means that the influence of that gene was so low that you only could find it as you increase the numbers, right?

So, it’s the same thing with smoking. If I looked at 10 smokers, I would not find the association. I’d have to look at millions of smokers to find the associations, so while there is an association, how strong is that association? That’s the kind of thing we have to look for.

B: Did you happen to see the study that looked at the Stone Age origins of MS genes, where they got very old DNA and concluded that the set of genes associated with MS emerged in the steppes of Russia in these pastoral populations?

S: Do you know Phil De Jager? He’s a big geneticist associated with MS and doing a lot of Alzheimer’s work right now. We’ve worked with him looking at these susceptibility genes.

In fact, we had a pretty large program called the GEM study – “Genes and Environment in MS.”

The idea is that we would take first-degree relatives of MS patients, healthy relatives, bring them to the NIH, and we’d do every test we could do on these people. Maybe they had some MRI signal, some immunological signal, or some viral signal, that says, “Because I know your mom or your dad had MS, we know you’re at risk.” Can we figure out what genes put them at risk? Never really worked. I don’t think the numbers were big enough, because the influence of those single genes are, by themselves, not high enough to show up.

B: I think it was a cluster of genes that they found emerged in this population. What intrigued me is they seemed to have emerged when that population started using horses. I wonder if there was some sort of encephalitis that this was protective against, and that the autoimmune nature of this is related to having to turn up their immune system to respond to an encephalitis virus to survive. Does that then put you at risk for autoimmune diseases?

S: The answer is I don’t know, but it’s conceptually possible.

B: Conceptually, that could explain why some people’s immune systems become overstimulated.

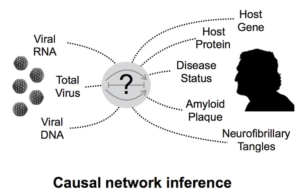

S: In our paper, what we found was very similar to what Alberto found, but we didn’t think it was specific. But you could use these technologies and the way he did it essentially is what’s called virus discovery.

If I took thousands of sera put them on these, I say I wasn’t expecting to find the signature of the virus, right? People have used it, in fact, that was the goal of that technique actually, to do that. So, we’ve done that. We have a patient, for example, has some problem. We did everything we could. We put them on the tool and find he has dengue virus. But we found that this guy’s case was associated with dengue, that is one way to look at the tool.

A friend of mine here at the Cancer Institute has looked using the same tool, based on some of our data, at hepatocellular carcinoma. You could get patient samples from before they got cancer. So, you have patients and X years later, they wind up getting cancer. Of course, they found using the tool that Hepatitis C was involved, right? When you eliminate that group with Hep C, he would look at the remaining patients and found an antibody profile that was a constellation of some antibodies. Some might be higher compared to a control group and some might be lower.

It’s like a signature, and what he found is that that signature was 98% predictive of liver cancer.

It wasn’t a particular agent. It was your response to the agent. Your response is your signature. As another example, your wife comes home with a cold, your kid gets a cold, but you never got sick. I guarantee you were exposed. I’m sure I could look at your sera and see that you had been exposed. But why didn’t you get sick? Because your immune system didn’t see it that the same way.

So those are the kind of things we’re thinking of more, and that was our paper. There may be a signature in which, by the way, EBV plays a role, part of the signature may be EBV, right?

But that’s not the cause of your disease. It’s your response to that disease based on your genetic profile, and that’s why it’s been hard. I’m sure you’re aware of the crazy people running around saying, “I’m not sick, I don’t need the COVID vaccine. Why should I get the vaccine?”

They just don’t get the way the immune system works, particularly to an infectious agent.

B: Given how complicated the immune system is, I think there are very few people who actually do get how it works.