As Chief of the Viral Immunology Section, NINDS, Steve Jacobson, PhD has spent the last 40 years studying the role of viruses in neurological diseases. Recent findings related to the role of viruses in neurodegenerative diseases, particularly EBV and MS, has made his dedication to this field seem particularly prescient. Dr. Jacobson shared his thoughts and experience in an interview with the neurology researchXchange™.

What do you make of the notion that MS is the result of local reactivation of EBV?

Steve Jacobson: It could be. It’s absolutely possible. Frankly, I don’t have a problem with that. The other aspect we’re looking at as immunologists is that it’s not necessarily that they are having a reactivation against EBV, but that the immune response is defective in MS patients. You reactivate EBV all the time, but you handle it very well. The MS patient has it reactivate normally, but does not handle it very well, so those are some of the defects in that area.

Bob Morris: My understanding is you’ve been a proponent of EBV playing a role in MS for a long time.

Steve Jacobson: So not a proponent of EBV, we’ve been a proponent of infectious etiology, I think it’s very different. EBV is one of the potential environmental triggers, but I think what’s going on is a persistent viral infection, which is what I came here to study – persistent viral infections of the nervous system. I did my PhD on immunopathogenesis in a mouse model of viruses. It’s 45 years later, I’m still doing the same thing, you know?

B: You were ahead of the curve.

S: I’ve been through the cycles. In any field there are always cycles, interest waxes and wanes. And now we’re in the cycle of, well, what about EBV? We’ve seen this before, and I’ve always said, “Don’t you think more than anyone, I’m the guy who wants to see this happen? Don’t you think this is exactly what would be the icing on my cake for, you know, 50 years of research?”

I have been fortunate working in the NIH, which means I’m not fighting for the grant out there. I don’t have to make a big deal in the press release. In fact, if anything, we stay away from that. I have no skin in the game. My life doesn’t depend on whether I got that paper in to get that grant to keep the machine rolling. We just follow our nose, and that’s what we’ve been doing for years. I guess we believe more in the incremental advances in science than the “aha” moment. In MS, we’ve been through lots of these moments.

B: Well, the Ascherio paper felt to me, as an epidemiologist, like an “aha” moment.

S: Yeah, I know, I speak to Alberto all the time. I consider him a very good friend, but we’re just on different ends of that. You could look at the same data in different ways.

B: When we talked to Marc Horwitz, he said that until the Ascherio paper came out, he had a hard time being taken seriously with his EBV research.

S: Tell me about it. So, I sit on the MS Society funding grant panel, and we would say we always want to fund the best research. Invariably, some of the best research was in the virology field, and they say, “Well, it doesn’t have that much relevance to MS,” so it’s knocked down.

It’s hard. Believe me, I have friends working on coronavirus who never got a grant, and then all of a sudden, you have a pandemic. So, you get funded to do it, but you take a little of that money to do the stuff that becomes interesting, and as a good scientist, you just follow what’s interesting. We just plug away at it.

I’m wedded to the idea that viruses are important in these chronic neurologic diseases, but for me to get to the point that this virus causes this disease is a big deal, right? That logic came out of the 80s, and I came on board in the 80s with HIV. In those days, when you got HIV, you died of AIDS. So essentially, once you found that agent, it was pretty easy from the epidemiology point of view, and I’ve worked with a lot of epidemiologists here. It’s a great lesson.

But just as important, if you never got HIV, you never got AIDS. That’s the real big difference from the virologist point of view, because now with EBV we’re dealing with the question of “How do you make the association with a bug that everybody gets?” That’s completely different.

B: As an environmental epidemiologist, we’re used to getting excited about a relative risk of 1.8, so seeing a relative risk of 32, and maybe even higher, is kind of staggering.

S: Yeah, but it’s very skewed. I could show you relative risk of HLA is even higher than that. Not everyone with that molecule has MS, but all the MS patients have an increase, right?

B: In the environment, we’re used to dealing with multifactorial causation, and to me this just looks like EBV is necessary but not sufficient.

S: You know, it could be one of the triggers. That’s what we said. There are other viral bugs out there that could also trigger in subsets of the MS patients.

B: If something other than EBV is the initiating factor, it would have to be incredibly highly correlated with EBV, assuming that the Ascherio paper is accurate.

S: OK, so here here’s the whole point. Everything correlates with EBV, because 95% of us have it.

Very few people have not been exposed to EBV, right?

B: That’s why they needed to have a cohort of 10 million to make it work.

S: And to find those thirty that didn’t have it. And I think that’s really why no one else sees that. No one else has that group. No one else could have that group.

B: It’s why it’s so hard to study.

S: That’s exactly right. I agree with you.

B: So to me, it was kind of a tour de force to do that study and be able to have those kinds of numbers, and see that relationship because you could only see it in that kind of a cohort.

S: I don’t disagree. It’s funny, we’re saying the same thing, but I think our terminology is different. I have no problem saying EBV causes it, may even be a leading cause or a trigger, but it’s not the cause of the disease because you need other things involved. Of course we have EBV, right? Because we’ve all been exposed to EBV, everyone’s been exposed to EBV.

B: Epidemiologists look at the word “causal” differently.

S: Yeah, I agree.

B: People say cigarettes cause lung cancer.

S: Correct.

B: That doesn’t mean that everybody that gets lung cancer smokes, or everybody that smokes gets lung cancer.

S: But in the infectious disease world, it means something very different. I use that metaphor all the time, right? Not everyone who smoked cigarettes gets cancer. So, in fact, the risk is in you. I can’t tell you what your individual risk would be. I can only tell you on a global scale, you know, if I look at 100,000 people. But I will not know whether you will get cancer from smoking if you are a smoker.

B: Well, let’s take a different example. Consider EBV infection. Most of the time, it doesn’t cause symptomatic mononucleosis, but you don’t get mononucleosis without EBV. So, I would argue EBV is the cause of mononucleosis.

S: I agree with you there.

B: I was very interested in the one case who was EBV negative and got MS; when I asked Alberto about that, he said that probably wasn’t MS.

S: There’s nothing I could argue on that.

B: It seems, from their study, as if you simply don’t get MS until you’ve had an EBV infection.

S: I understand, but I’m just saying I’ve never seen anybody in the real world that doesn’t have EBV.

B: I get that, and that’s why it’s so hard to study.

S: I agree, that’s exactly what I’m saying. I’ve always said, as someone who measures, the epidemiologist is only as good as the assay that you’ve asked for, right? When I look in a sheet, whether it’s negative or positive, I don’t trust it till it’s done in three or four different ways, particularly if it’s something very odd. I can’t tell you how many times people have sent me a sample they said is negative and we found it to be positive because we have different assays.

B: So that would suggest that maybe they need to retest the set of their EBV negatives.

S: And I’ve asked for that numerous times, but the samples actually go somewhere else. He doesn’t even hold the samples.

B: I’m sure those samples are like gold.

S: You understand. I give him so much credit because I’ve known another group at the DoD who’s looked at that and has adjudicated every one of the MS cases that they get from the DoD, right? Just because there’s a code for MS, sometimes that’s all they read. Someone has to go to the original records to actually see whether it really was MS or not.

We have a very large clinic for MS. You cannot believe how many patients are sent to us with a diagnosis that don’t have it, and some patients with other diagnoses that in fact do have it. It’s insanely common.

B: It’s sort of a diagnosis of exclusion.

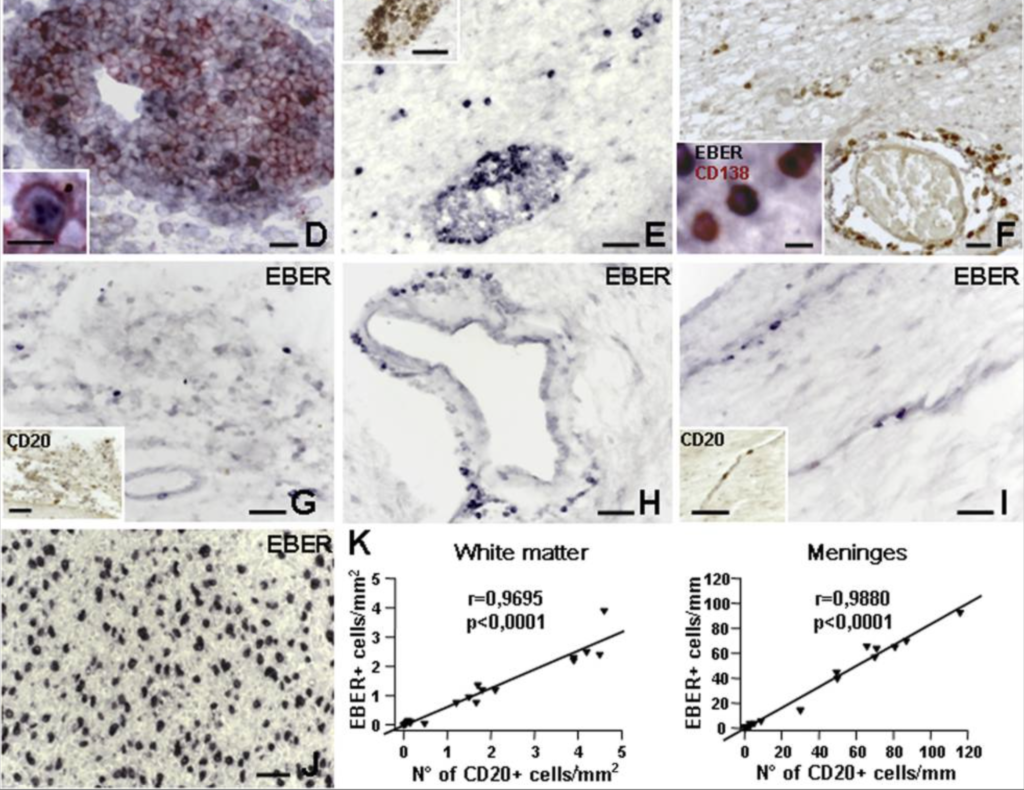

S: It used to be a diagnosis of exclusion. It was really a diagnosis at autopsy, frankly, you have to get the brain and look at it. Now we have the MRI. We could do a lot more, but I’ve looked in cerebrospinal fluid for many, many patients and we are looking for antibodies to EBV or other viruses that we could see in the CSF versus the blood. And there are differences in all that. If you look at our paper that we that just did in response to Alberto’s, we found very similar observations, but it was not necessarily specific for MS. That was the problem. I have another disease in which EBV was just as prominent. So does that mean EBV was causative in those? It’s much more complicated from an epidemiological point of view. If the numbers are strong enough in enough studies, you could say, “Is this really the cause of the disease?” And I will have the patient asking “Hey, doc, do I have a virus? Can I give it to somebody? Will I get it? Can you give me a drug to stop it?” It’s really not quite that simple.

B: It’s clearly not simple. EBV is necessary but not sufficient, and it depends very heavily on the genetics and on other factors that we don’t fully understand.

S: But there are now a subset of neurologists – Alberto, you know, and Gavin Giovannoni – who really are going around saying, “This is the cause of MS” to the patient populations. That’s where we have problems.

B: My read from the epidemiology is MS is a rare sequela of EBV infection.

S: And we’ve been through this with chronic fatigue syndrome, that chronic fatigue syndrome is a rare sequela of EBV infection. We have looked at “long COVID,” that you need an EBV infection in COVID to have neurologic complications. We have seen this time and time again – “Alzheimer’s disease is a rare sequela of another herpes virus infection, ALS could be a rare sequela of another virus.” This is what I’ve been doing for all these years. Proving this is the hard part.

B: What do you make of the notion that MS is the result of local reactivation of EBV?

S: It could be. It’s absolutely possible. Frankly, I don’t have a problem with that. The other aspect we’re looking at as immunologists is that it’s not necessarily that they are having a reactivation against EBV, but that the immune response is defective in MS patients. You reactivate EBV all the time, but you handle it very well. The MS patient has it reactivate normally, but does not handle it very well, so those are some of the defects in that area.