“I do believe in the end that, after all of these associations, the only thing that I’m going to believe is clinical trials. Can I interfere in the disease, based on some mechanism I have proposed? Then I have a real outcome effect, and that’s ultimately from playing in the lab for 40 years. You really want to help patients. You don’t want to go back to the patient to say, I really can’t help you.”

Steve Jacobson: Mike Racke had a really nice model in a mouse, right? The mouse got sick. It wasn’t MS, but they did get sick, and we’ve replicated that same thing in a nonhuman primate. You have the exact same thing with another virus that was associated with MS – Herpesvirus 6A, a beta-herpes virus. Again, a very common virus, we all get it as kids. Everyone has antibodies to it, or 95% of us have antibodies to it. I’ll gladly say everyone has it because I’ve just never seen anybody that doesn’t have it. But it’s another virus that we’ve been interested in.

I have a great first slide of all the viruses that have been associated with MS over the years. There’s been a lot of viruses that have been associated with MS, so you kind of have to bring that historical perspective to the new world, particularly with the advances in bioinformatics. I’m in agreement with you, and EBV may be necessary. Although again, the word “necessary” – I like to think of it as that you may need some environmental influence, some environmental trigger, and viruses are perfectly reasonable to think of for that, but they may not be the only environmental trigger.

B: The real importance seems to be the possibility that if we could get an effective vaccine against EBV, maybe we could get rid of MS.

S: Well, it’s funny you said that, because I came to work at NIH in 1980 on measles virus, and measles was also associated with MS for years based on the epidemiology, which you know as an epidemiologist.

There was the Faroe Islands, right? There was never MS on the Faroe Islands until World War I.

When the Brits came and brought their dogs with them, the dogs had a virus called canine distemper virus, which is a measles virus. Now they get MS, so therefore, MS was triggered by measles virus. I did a lot of work looking at measles, and we hoped that when we all started getting the measles vaccine, we would see a reduction in MS. But we have never seen that. The measles vaccine is not associated with reduction in MS.

So going back to should whether be vaccinating people against EBV, I’m doing a clinical trial. And we are looking to see if we can use an antiviral drug. We’ll see.

B: What do you what do you make of this recent study that suggesting that the shingles virus vaccine protects against dementia?

S: I saw that and was contacted by a news organization about it. We looked at that in depth. That is an amazing study. They looked at 800,000 records and can distinguish people born just a week apart based on who got the shingles vaccine. You know, the data is the data.

B: I know you’ve studied herpesviruses in various neurodegenerative diseases. So, I’m just wondering from a virologist/immunologist point of view, what do you think of it?

S: It’s funny you say that, because the way an epidemiologist looks at it is different from the way an immunologist may look at it, from the way a virologist may look at it, even from the way a clinician may look at it. You know, we’re all touching the elephant.

There was a study that came out on this other virus I worked on, HHV-6, showing it was associated with AD. It came out in Neuron. This is a beautiful study where they did 1,200 brains, three or four regions for each brain, from patients with Alzheimer’s and from controls. An amazing study using bioinformatics. What I love about those is that they have no skin in that game – the data are the data, right?

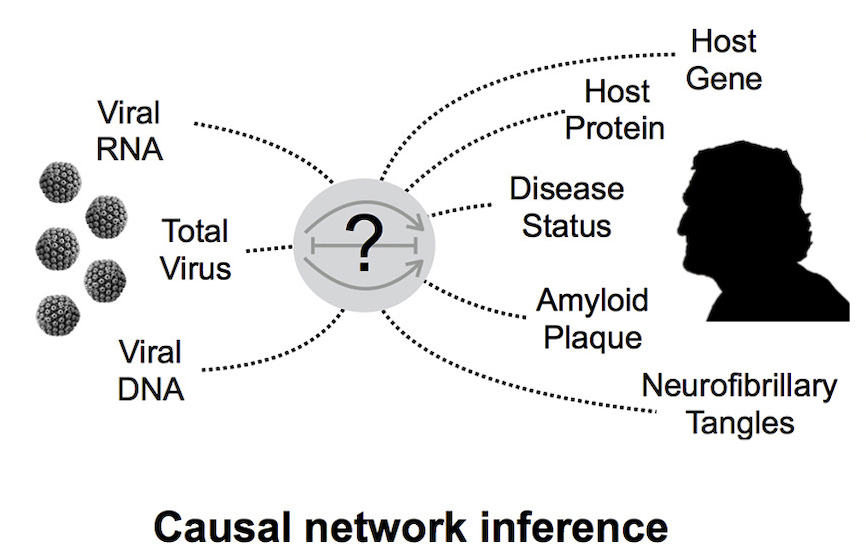

It was an RNA-based study and they came out with this HHV-6 claim. There was no one on the paper even knew what HHV-6 was. We worked on HHV-6. Then we wrote a paper to Neuron because we were able to get those exact same brains that were in that paper. The way a virologist looks at it, we tried to amplify the virus. We were unable to do that. We could not find the virus in those patients. So again, the virologist would touch the elephant by doing a PCR assay, right? An immunologists would touch the elephant by doing antibody assays. The bioinformaticists will do a big genetic screen. The epidemiologists look at 800,000 medical records. And so you almost have to do this very orthogonally, you know, to have different approaches. Any serious evaluation of causality needs all those pieces to fit together.

B: This is clearly something you’ve invested in and studied for a long time. Do you suspect that most neurodegenerative diseases have an infectious origin?

S: Yeah, well, that’s a great question. Given my conservative roots at the NIH, I would probably not want to phrase it that way.

B: Now you’re talking like an epidemiologist. We’re absolutely trained that you can never say, “A caused B.” You just say there’s an association.

S: So you know, we have a pretty big institute called the NCI out here. That is a really big group of epidemiologists. Let me give you an example that’s happened with the NCI. There was an outbreak of a cancer in a certain area – Nevada, I think? And then they thought, “Was this related to a virus?” Because they all got some viral infections. And NCI sends a team out there. The CDC sends a team that’s all epi kind of people, and they bring the samples back to the lab to say, “Hey, lab guys, what could you show?” And sometimes it’s very hard to show that. When I think about these kind of experiments, what I think about is that if I would do an experiment and I don’t find something, what do I say? I’ve always said to everyone in my lab, “As soon as you say this virus that causes, or this virus is associated with, this disease, you’d be sure the next paper will come out to say this virus is not associated with this disease.”

B: That’s how science works, right?

S: That’s how it works.

B: That’s what you can get published at that point.

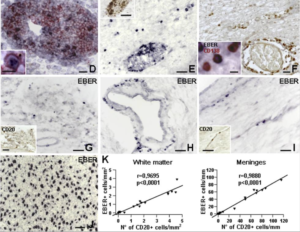

S: Yeah, but that was never my thing, because there’s lots of reasons I can’t do something. I don’t have access to Alberto’s samples, right? He may go to a different place. He has different technology. It’s just not compelling to say I can’t do something. I’m not very good, maybe that’s why I can’t do it. I remember the original papers, these great original papers that had EBV in the brains of MS patients. I know the groups of Serafini’s and Aloisi’s very well. I’ve been to their labs, wonderful, really legit people. Another group, Dave Hafler’s at Yale, they got the exact same brains from those exact same sections, got the same antibody, and could not reproduce what they did. So what do you do? You get a third person.

I do believe in the end that, after all of these associations, the only thing that I’m going to believe is clinical trials. Can I interfere in the disease, based on some mechanism I have proposed? Then I have a real outcome effect, and that’s ultimately from playing in the lab for 40 years. You really want to help patients. You don’t want to go back to the patient to say, I really can’t help you.